Evernote, Dropbox Paper, and The History of Word Processing

The recent history of the software and services we use to retain text, and how their development affects our behavior on the page.

I have only once in my many using years been gripped by the fear of the Lord because of a software-related event. I was cruising my pitifully ugly Google News feed on an October afternoon in 2015 looking for the last little bit of material for the evening’s episode of Drycast, when I happened to spy the words “Evernote is in Serious Trouble.” I doubt I screamed or anything, but I definitely remember experiencing a very real, full-body shot of adrenaline because my entire creative life was contained at the time within the nearly 40,000 notes I’d amassed on my Evernote account since the service’s open beta in 2008. In fact, I was in that very moment using it for the live show notes and so began to wonder how I could possibly continue if Evernote were to be suddenly killed dead. For better or worse, though, the “unicorn” would indeed survive to see its tenth birthday this year, though it’s arguably been eclipsed by the notetaking, journaling, and word processing services its features predated and for which it was the most significant forerunner not so long ago.

I’d been using the cloud-synced notetaking service for all of my composition and research gathering since Junior High, when I thought myself extremely clever with my cloud-syncing, iPhone-native notetaking app when I’d watch other students struggling to find a flash drive or log in to their email on school library computers. Since it worked with any browser and my password was memorable (before the brute force apocalypse and the need for password managers,) I could access my documents, mp3s, and images from anywhere, which was actually a pretty big deal — especially as more research and notetaking was required in high school.

Yes, 10 years later, we are swamped with infinite duplicates of documents from our personal clouds, which are now inescapable and plenty — they follow us around from our pockets, purses, and backpacks and rain notifications down upon us for single punctuation mark peer edits, unnoticeable modification conflicts, or sometimes just for the hell of it. There are now what seems like infinitely many available ways to enter, edit, and publish text from wherever you happen to be, and most of them are free, but very few are actually pleasantly executed tools — all of which can all be said of most types of software now. Since tech publications (and even tech bloggers now,) aren’t doing software reviews anymore because you won’t click on them, the task of comparing between the lot so that you might be spared having to mess around with all of them to find out for yourself — the function of consumer journalism — has fallen to myself, alone because the Fear of The Unclicked is not known to me.

To assist me in bearing this terrible burden, you can allocate 1–3 minutes to take the survey I created about the text-entry tools you use to determine which tools people use at different points in their writing process and across several uses. It would be very much appreciated.

Feature Fucked

Reading this via printed PDF, your hypothetical 100% offline grandmother — the successful children’s book author who needs word processing but doesn’t require connectivity because she doesn’t do research or correspond with anyone — might ask well whatever was the matter with Microsoft Word? Surely I don’t need more than that! Technically, she’d be correct in a major sense: Word has been able to sync via Microsoft OneDrive between PC or Mac with iOS or Android for a while now, but I wouldn’t vouch for the latter for any use other than reading or very lightly editing a document because the relationship between the mobile apps and their desktop counterparts is inevitably strained. Because Microsoft Word is such old software, it’s filled with some obscure functionalities I’m sure even its creators have forgotten. Over years and years of development, these tools have been stacked on top of one another so that actually mastering the labyrinth could be a college major in and of itself.

Basically, you can tell your grandmother that Microsoft Word is a huge old bitch, but it’s still the industry standard for formatting and publishing works at the end of the line. As you can see from our survey results, 58.1% of you use “legacy” word processing software to finish up your first drafts (as of May 30th,) which makes you more modern than even a slightly-older population, I’d wager.

While we’re on the subject of the old hag, it’s worth pointing out how ridiculously behind the times its open source “alternatives” are. OpenOffice’s last major update was the release of version 4.0 in July of 2013, and it’s not correctly scaled for the small, high-DPI displays sold at just about every price level, nowadays. It was okay when I couldn’t afford to pay for a license in high school (and saw no reason to,) but it now looks sort of awful, especially considering that the version of Office (and therefore Word) to which I’m comparing its screenshots is actually also from 2013.

The other, “fresher” open source option of the moment is called LibreOffice Writer, and its suite has been attracting a fair amount of praise — I think “every bit as good [as Word]” is taking things a bit far, but its sixth version looks significantly better than OpenOffice on my machine, at least, and generally operates more smoothly as well. That age-old banner of Open Source won’t matter for much longer, though, if all kinds of software continue to be abandoned and substituted with Progressive Web Apps for no damned reason. Considering how much time some of us have already spent in front of Word, it’s no wonder we’re spoiled: even my 5-year-old edition of Microsoft Office syncs with the app on my iPhone (with some pleading,) and looks extremely crisp. As far as paid featured desktop-class alternatives, there’s just one more: WordPerfect, which I have never used or heard anyone else mention.

The Hybrids

When it was conceived, Evernote pioneered the recipe that now serves as the foundation of the feature development in today’s notetaking and journaling applications, as evidenced by CEO Phil Libin’s unapologetic use of the term “life-logging” in 2009, which sounds bizarre in retrospect because we’re now well-accustomed to easily “snapping geotagged photos” (smartphones had always included location data in their photo files’ meta, but Evernote was the first app to give a user access to the data on their device,) “making voice notes,” or and organizing text notes via advanced categorization and metadata-enabled searchability. These features are essentials in the apps you could accurately describe as “life-loggers” available for download now. Snapchat’s “Memories” especially come to mind, and I’ve long argued that we should blame (or praise) Evernote for beginning the era of eternal memory.

The iPhone OS app’s design would even influence Apple’s own additions to its native photo and note applications in iOS7, much further down the line. Its technical doctrine of on-device storage coupled with syncing via The Cloud would inspire both Microsoft’s OneNote and Bloom’s gorgeous DayOne. There was even a “full-featured” Linux-running offshoot called NeverNote.

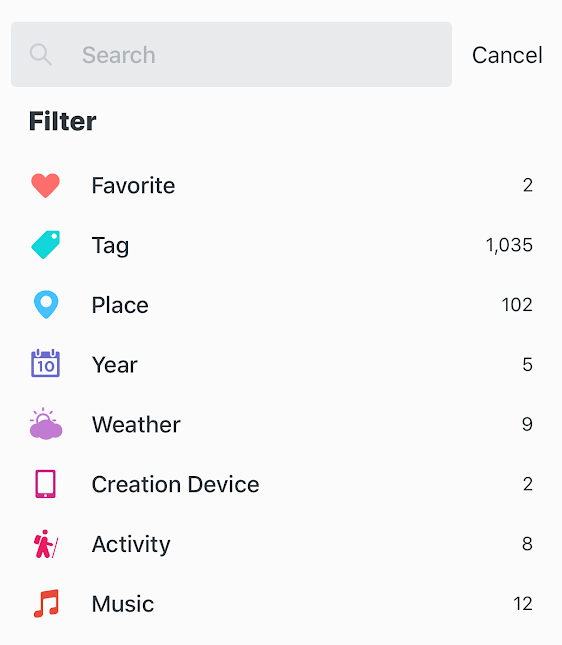

In contrast with Evernote’s relatively busy design, DayOne has been the best-looking app of any kind on iOS for years. It shipped with the same sort of extensive categorization, but it’s only ever been available on iOS, Android, and OSX — probably because Windows simply doesn’t look good enough. Should you wish, it will add detailed metadata from the moment you begin each journal entry including precise-ish GPS coordinates, an overview of your location’s weather at the time, whether or not you were moving, what song you were listening to, and your step count for the day (now from the Health app.) You have the option of viewing your journal chronologically, by location on a map, or in a social-esque activity feed, and yes — its search function can be filtered by any of these datapoints.

In 2015, Bloom added iCloud syncing and multiple journals, further closing the functionality gap between the two apps on paper, yet plenty of users continue to tether between the two using IFTTT (including myself for all my Twitter favorites, just to compare.) Within the somewhat forgotten niche of the “life-logging” utility, DayOne is superior and serves well the self-obsessed user who find the little details of their life to be extremely interesting. Last Spring, they introduced the option to purchase a stylized physical book of a user’s journal from within the app. As it is currently priced, the 2,674-page book I previewed today containing every single Tweet I’ve favorited in the past 5 years displayed in a delicately-formatted layout would set me back over $365, and would have to be split into 5 separate books (as per the maximum of 400 pages each.) Since I find my life very interesting, I’ve made a note to myself to proceed if/when I ever have that sort of money to throw around.

For the 67.7% of you who use digital notetaking or word processing software when you “want to remember something,” DayOne is the best option available because of its search function and satisfaction-of-use. Though Evernote was once the only app that could “handle everything everything in your head,” it’s a different experience entirely — tailored for work applications, if anything, since DayOne’s growth spurt. The company, itself hasn’t exactly been managed cleanly, either with layouts in 2015 and a privacy scandal in 2016, but then again, what billion-dollar company doesn’t have its controversies?

Despite having imported my huge catalog of Evernote entries into DayOne, the former often gets stuck, and it’s retained the most irritating habit of all the software mentioned in this column. Because synced entries in Evernote are not live-updated like those in Google Docs or Dropbox Paper, it’s possible to modify or add to a note on one device while it’s open (and static) on another, which is addressed by either duplicating the most recent entry and filing it in the default “Conflicting Changes” folder, or pasting the duplicate of the entire contents above the “old” content in the note, separated by a horizontal line. I’ve yet to figure out the behavior that triggers which fix, but I don’t particularly care — I’ve decided to restrict my Evernote use to my desktop, absolutely. If I haven’t articulated it well enough for you to form a visual, just trust me: it’s very, very annoying, and it should’ve been addressed years ago.

It was my stepfather who told me about Evernote and signed me up for that beta. Both of us were then the sort of people who experienced extreme satisfaction in archiving and categorizing stuff (which is probably the most straightforward way to define nerd,) but he was especially and absolutely enthralled with its Web Clipper function, which allowed the user to save webpages with “context” — both the metadata (source URL, date) and contents in “the text, images, and links” via their Firefox extension, which was revolutionary from our perspective, and certainly beat the hell out of stuffed, ugly bookmark folders or printed-to-pdfs. However, Web 2.0 was a younger, then and significantly more lithe — the average web page is now 10 times larger (disclosure: “average web page” is a somewhat misleading term, though I think we can probably agree that it’s too fucking big, regardless,) and it’s long past time for us to accept that this technology is no longer a reasonable solution to saved images.

Though development on the Web Clipper appears to have continued — it’s now on Version 7.something — the vast majority of the pages you’d want to save on the web (except for Linkedin, apparently,) show Evernote’s age as it attempts to clip them — often taking several minutes to yield the product, which is always broken as hell. Don’t take my word for it, though: another one of Evernote’s less-discussed features technically makes it a publishing platform because I can share a note from my account with you, the world, via this public link. It’s a clip I took a year ago of Wired’s profile of Jad Abumrad, and you’ll notice that it isn’t completely unreadable, but it is ugly and broken. Even after last year’s update, it’s still clumsy, slow, and virtually unusable without a stellar data connection.

Archive obsessives, I know that Evernote could have become part of your system and over time, you may have built a gargantuan library within it — the perfection of your tagging system’s efficiency and your categorical format’s consistency making it such a treasure that you might think of it in times of duress to calm yourself. I’ve allowed myself to continue using it exclusively for notes in my novel project, so I do understand that it may represent tens of thousands of hours of your time and that losing it would cause you tremendous grief, but… it’s time to let go and better your life by exploring the selection of alternatives and their superior capabilities.

As you’d expect, software has changed a lot since 2010, and the choices available for word processing are now abundant and relatively diverse. As for web clipping, in particular, I would suggest your new browser Vivaldi and its super capable full-page capture feature, which I’ve used for everything from snapping a 25.1 MB, 30,000 pixel-high PNG capture of all Extranet data in text form to the photo specimens we submitted to Fonts in Use, to crisp snips of full words. For comparison, here’s what it captured of that old Wired post on Jad. You’ll notice that while the image is relatively large, none of the article itself has been lost (aside from the featured image, on Wired’s end,) and the resolution is fine enough that you could still crop out quotes or smaller shots to share if you discovered something later. This ability of Vivaldi’s still feels like magic to me, and there are plenty of other reasons to use the browser, but I’ll save that discussion for a later date.

I could cite plenty of pseudoidealistic reasons to never use Google Chrome, Google Docs, Google Keep, or any other Google product, really, mostly because they all look like shit, their browser is swallowing the internet, (along with their “accelerated mobile pages” project,) and just about everything the company was built on — along with what they plan for the future — is completely (and sometimes even explicitly) opposed to The Open Web, good design, and humanity as a whole. However, I fully realize that idealism doesn’t mean shit when you’re just trying to get the job done, so let’s talk about Keep and Docs.

Google Keep is part notetaking service and part streamlined, modernized, hassle-free execution of Evernote’s Web Clipper. If you’re already using Chrome or you’re desperate enough for the ability to clip web pages without switching windows for whatever reason that you’d change your browsing habits entirely, you can add its extension to the top task bar — right next to Evernote’s — and use it any time you feel that old archivist itch. The extension will very quickly and smoothly clip the title and URL, along with whatever of your own text/tags you feel like using, but it will not attempt to capture any of the web page’s content (Google already has it somewhere, anyway.)

Like all of its kin, Google Keep is particularly savvy with integration: you can immediately send your clip to a Google Doc, set a reminder, add a collaborator and even draw on any entry. Its party piece in this Tactile Era of touch-enabled laptops and keyboard-equipped tablets is its ability to digitize handwriting or “grab image text,” a novelty technology called Optical Character Recognition, which has been tickling our most stale fantasies for centuries, now. Though I’m sure it’s genuinely appreciated in a handful of especially quaint use cases, somewhere in the world, there’s never going to be an at-scale application for this sort of thing. I know my handwriting is bad, but if Keep can’t “grab” it reliably, there’s not much sense in using it at all for me, though Google’s Academy for Young Algorithms will certainly make sure to save every one of my motions to capitalize on my time (or yours.)

Microsoft OneNote is as clunky, busy, and buggy as Google Keep is quick and uninspiring, but that’s probably because it’s much much older than I remember. To demonstrate its web clipping function, I clipped the OneNote portion of PCMagazine’s Microsoft Office 2003 review and exported it into a PDF, which isn’t a straightforward process, but is it useful? No. Because it’s a PDF, it’s almost unreadably low-resolution, yet manages to weigh 1.2 MB. My (cropped) Vivaldi capture of the same page is 988 kB and nearly impossible to tell apart from the live experience, so why are we bothering with OneNote at all? Well, according to Preston Gralla for ComputerWorld (the last tech site still publishing worthwhile software reviews):

It bristles with note-creation tools for drawing, recording audio and video, scanning images, embedding spreadsheets and reviewing the edits of others (although the abilities of those tools differ somewhat depending on the platform). In fact, its note-creation tools are more comprehensive than Evernote’s.

And we begin to see OneNote’s place as the feature-heavyweight of synced notetaking applications.

The organization-minded will appreciate OneNote’s basic structure. You create individual notebooks; within each notebook, you can create section groups that contain multiple sections. Each section has individual pages, with each page a separate note. It’s ideal for organizing content with a logical structure.

Then again, dearest Preston goes on to express his adoration for Evernote Web Clipping shortly afterwards and he did so just last year, so I won’t really claim to know what’s going on with him (he’s a legacy tech journo.) In my experience with twenty-somethings and younger, the more committed an artist or writer is to their craft, the less interested they are in its tools, but it’s the young ones who need great tools the most before they’re able to settle on and pin down their process. There was only a single writer (3.2%) surveyed who answered “when I want to DIGITALLY record something to remember, I use…” with “the ‘compose’ function (to publish immediately and/or save for later as a draft) of a web-based text sharing service (Twitter, Tumblr, Medium, WordPress, Facebook, etc.),” and one other answered “another text-entry field on my device where it will be saved for later,” which four users (13.3%) said they use to “Brainstorm” digitally.

By Question Set 3, the two alternative answers were dropped and for “Outlining” digitally, 45.2% of surveyees use legacy word processors, 35.5% use cloud-based notetaking apps, and 19.4% use the default notetaking program installed on their device. In omitting alternative options earlier and including web-native CMS editors later, I inevitably shepherded answers within a moderately-wide berth of where my own assumptions would lead their process. It’s interesting that for the last prompt, “to make the last modifications to my final draft, I…” a whole 35.5% reported they would still be using a cloud-based service instead of a legacy word processor (58.1%) or CMS editor (6.5%), which would suggest that the functionality of these new e-enabled methods of composition has become truly important, indeed.

Though it’s not necessarily unreasonable, it astounds me to consider how many Online users actually compose original drafts of huge works exclusively within publishing and blogging services like Medium, Tumblr, or Reddit, even. We currently cohabitate a literary sphere with impossibly massive works of fanfiction that far surpass anything God or The Classics established in the past, and it’s a wonder how many sour habits have crept into the writing world as a result. For the sake of the experiment (and my own education,) I posted some of my recent work on Medium and found its composition UI much improved from what I remember and comparable in many ways to those of more recent dedicated document editing/notetaking services, but there’s still whole set of abstract, less-than-technical reasons not to publish on Medium, much less compose there.

Briefly: instead of “defining a new model for media on the internet,” CEO Ev Williams and company ended up creating an isolationist community with hellishly-skewed priorities in craft. Virtually all of what’s actually born on Medium is of a certain soulsucking, less-than-productive quality (notable exceptions include Ryan Dell, Dave Pell, and work from marginalized voices that would not otherwise be written or published.) Though their founding principles of ad-model disruption are redeemable and entirely sincere, I’m sure, their result doesn’t actually solve anything at all, especially after last year’s layoffs and refocus.

As for Tumblr and Reddit, I’m afraid I’ve never been capable of truly understanding either, but I did blog extensively about cars for the first time 5–6 years ago on the former when it was one of significantly fewer fee-free options for digital publishing, and even then the experience was already casting doubt on the true necessity and existence of blogging platforms like WordPress — especially for web development-abhorring peons like I was at the time. Now, its iOS app is gorgeous, and its editor has ended up rock-solid and surprisingly versatile, yet the state of its community, also, leaves one with little reason to publish aside from a sortof isolationist desire to contribute to the community itself, for Tumblr’s sake.

This is where WordPress should outshine everything else as a pure, open-source Content Management System for any and every use by any and every folk with server space, so I thought I’d try out my own fresh, ultra-connected install to see how its experience has changed. In word processing terms, its iOS and Windows clients are lightyears ahead of where they were a few years ago, but to take full advantage of them, one must allow WordPress’ own software access that’s not Open Web at all. For light, minimalist personal blogs, a WordPress site offers much more control over one’s intellectual property than Medium or Tumblr, but it’s also significantly less independent than it once was. A quick inspection of my little experiment reveals that 5 out of its 6 content sources are from Google or WordPress properties, leaving only one for my actual server. This means I can accomplish a lot using just their apps, and my work will be distributed among “billions of posts” across WordPress dot com (to be found by absolutely nobody, I suspect,) but the post editor within the CMS itself has never functioned quite so versatility as it does right now. And yet, neither WordPress nor any of the software I’ve covered thus far achieve much progress toward an ideal, comprehensive word processing solution.

That’s why I’d like to talk about Dropbox Paper, which has been my own browser’s homepage and primary text editor since its public beta went live in August of 2016, and it’s very hard not to dote on considering that it is definitively the single most useful software addition in my whole computing life. It’s a live-updating exclusively web-based (for now) service with an emphasis on collaboration, just like the industry-standard monstrosity that is Google Docs, but it’s been designed from the ground-up to perform best the operations you need most from a word processor in 2018, which doesn’t include advanced layouts, fine-adjustable paragraph and/or letter spacing, Excel integration, or voice dictation, but simply… typing and re-reading and editing. You’d be surprised what a handy productivity catalyst can become of a simple white, live-updating space without distraction available no matter where you are or what device you’re in reach of.

Virtually all of my “process” is now conducted within Paper, and I’ve never before experienced such an unconscious assimilation of use. I write about software because I’ve used a lot of it and I’ve been able to count on my ability to find fundamental mistakes/designed ignorance in most everything. Dropbox Paper, however, is so keenly perfect for my own needs that I slipped unconsciously into total, daily dependence upon it without noticing the transition at all, which has never, ever happened before. Notes can begin from blank Text/Title fields to Brainstorming, Meeting Notes, and Project Overview templates. In April, the team introduced the ability to “templatize” any document, which I’ve yet to explore but will no doubt make full use of for show notes when Futureland is revived. There are also Evernote templates, yes, but you cannot create your own, and downloading them is an unnecessary pain in the ass.

Landing on the root, you’ll see Folders, Starred Folders, Starred Entries, and Shared Documents all displayed chronologically by modification date. Instead of tags, categories, or “notebooks,” Dropbox Paper’s folders are its singular method of categorization, and they are astoundingly sufficient, even when editing multiple documents simultaneously or digging through professional and personal entries within a single account — all thanks to its search function, which is super-swift and superior to any other service because of its profound simplicity. It’s one of many experiences which laughably shame past efforts in the design of these tools: without any customizable search filters or metadata and by sifting only through title, content, and author, any note in Paper can be found instantly no matter how dated or obscure. I doubt I’ve yet to top 1000 entries quite yet (there’s no easy way to count, and why should there be, really,) but on several occasions I’ve found years-untouched, untitled documents within seconds — a process which has never been brisk or convenient in Evernote.

Though Dropbox Paper wasn’t necessarily designed for composing 5000+-word longform, it’s by far the best tool for the vast majority of the pre-publishing process (to a reasonable extent, of course — I wouldn’t use it for a screenplay or novel manuscript.) It’s rare for me to utilize its mastery of collaboration, these days, but there’s frankly little reason to go anywhere else — including Google Docs — considering that Paper documents can be bound by the same viewing and editing permissions: by individual entry or folder, marking live modifications with clean, color-coded initials in the sidebar, by email or rogue URL for editing, commenting, and/or reading. (The comments interface is the best I’ve ever seen by a wide margin.) Users can be assigned and “pinged” for tasks using “@,” and it’s reasonable to assume that permissions won’t ever present an issue for my own use considering they haven’t already. To a limited extent, notes can be easily “published” via shared links yet remain editable in realtime, making Paper perfect for obscure-but-public reference documents like our style guide and redirects catalog.

From the onset of use, you’ll marvel at how fucking fast and smooth the in-browser experience is regardless of your device’s age or dimensions. Surprise surprise — the iOS app works just as smoothly and is laid out vaguely like a Twitter client. “Browse” — the chronological timeline of documents — occupies the leftmost bottom button as “Home” — the main timeline — does in Twitter’s app, and “Notifications” is likewise the same icon (practically) in the same position in both, and the items themselves are even grouped with rich card-looking content previews. Perhaps these nods to my Twitter muscle memory have contributed to my own unusual bias, but I suspect it shares components with a particular demographic of professional writers. As I understand the day-to-day activities of a feet-on-the-pavement reporter, Dropbox Paper is a necessity in a ridiculously all-encompassing sense. With its Slack integration, super high-usability design, collaborative modularity, ultra copy-and-paste-friendly text, smooth hyperlink behavior, light weight, and ultimate compatibility, it should be evangelized as a no-brainer option in journalism. Fuck a Bic & steno.

Web Clipping may be completely alien to its vocabulary, but you can drag and drop documents in just about any format for a beautifully-embedded preview. Conveniently, they won’t even count against your Dropbox upload quota: “Dropbox Paper doesn’t place a limit on the number of docs you can create, and includes unlimited version history regardless of the Dropbox plan you are on.” Naturally, this is subject to change in the future, but I’m 95% positive that Paper has yet to refuse any of my uploads because of their size or format, and many of mine are extraordinarily huge.

There is a perfect power to Paper which I can only beg its stewards to leave unmolested for as long as possible. If I was a billionaire, I’d immediately purchase it from Dropbox and leave everything to the company — revenue, janitorial development, user data, etc. — except the right to make any significant feature or functionality additions to the user experience, as I have never before felt this way about a single service or program… ever. I’m not sure if I should keep quiet or incessantly kiss ass, but my interest undoubtedly lies in preserving Paper as it is. If you’re left doubting my own testimonial, there are a billion throwaway “Ditch Google Docs for Dropbox Paper” posts across the B and C-list technosphere. Gizmodo’s, for instance, notes Paper’s superior formatting freedom, intelligent footprint, incredible embed flexibility, and… independence from the terrible Google God.

Right now, one’s choices in notetaking apps for iOS are almost too varied. There’s Zoho Notebook, which claims itself to be “An App Store 2016 Best App of the Year” (falsely, it would appear.) I recall installing it on my 6S Plus, then, after spying some screenshots of its multicolored notes, but I failed to find room for its use. When the (completely useless) Files app was added with iOS 11, I played around with it for a bit and somehow ended up setting Zoho as the default application to open PDFs which inadvertently launched my 8 Plus into an infinite loop of “Open __ in __?” prompts that eventually required deletion of Notebook in order to view them at all. I tend to especially adore these programs in their early, innocent versions when they smell most of innovation before their creators are inevitably brought back to our filthy reality when their VCs start expecting money. Zoho Notebook should have bewitched my affections, but my short trial was clunky and disastrous and those beautifully-colored layouts weren’t quite worth the trouble, so they were missed — to no consequence at all.

The latest favorite is Bear, the Markdown-supporting app with which The Verge’s Casey Newton replaced Evernote for his own use, last year. His authority in writing copy at huge volume is notable if only for his daily newsletter on the business of social media, which is always unfathomably gargantuan and clean.

Bear lets you tag notes by adding a hashtag to a word anywhere in your document; you can add as many as you like, and then browse them later from the left rail. You can export your notes as PDFs, rich text files, HTML documents, or even JPEGs. And it supports ultra-nerd automation, so if you use an iOS app like Workflow [now Shortcuts] you can create shortcuts to your notes.

DayOne’s own markdown support and exporting capabilities surely make it Bear’s predecessor. JPEG exports are a nice touch and they reflect awareness of what power notetakers like Newton actually do with their software. If I had not already chosen to depart OSX, long ago, I would seriously consider downloading the app on both platforms and paying its monthly $15 membership fee to try out syncing, but I suspect Google’s moderate but noticeable influence on their design would quickly prove to be a turn-off, personally. I had a go at Bear’s free iOS experience and saw little functional difference from DayOne — if anything, text didn’t look quite as sharp — but its reported integration with Siri Shortcuts is intriguing. (Apple acquired Workflow last year, absorbing it into its upcoming iOS 12 release as Shortcuts.) I’d suggest you give it a try — especially if your desktop-class machine is a Mac — and for your sake, I would hope they choose to utilize the power of the modern browser with a web interface in the future. “As a writer, I work in text, and text ought to be simple,” Newton opined, likely with more brevity than I’m capable of in this discussion.

Much of anything has yet to be written about these offerings in 2018, but I must insist both regular and intermittent writers alike give Dropbox Paper a try. I suspect you’ve less “privacy” to “lose” than you would in Google Docs, and its sublime function as a writing tool extends from workplace collaboration to shared grocery lists with your SO and long, image and hyperlink-saturated works like this one. It’s very difficult to break — even by pasting fragmenting code or Zalgo text; it’s never out of date, and always a short, teeny pageload away even across the worst of connections. As someone with an unhealthy obsession with his written work, I can tell you that its UI is by far the most anxiety-relieving I’ve ever used. As an alternative to Google Docs, I would point out that 1) Docs supersedes Paper in sum features significantly less than you’d think and 2) for the one or two weird formatting challenges it fails to complete, neither Microsoft Word — the old bitch — nor Docs are going anywhere, and Paper exports to both of them directly.

The Future

Curiously enough, I was required to use every single method of text retention of which I am capable in the course of writing this piece, as I tripped over my laptop’s charging cable — a physical connection, yes (and with substantial leverage) because Apple won’t allow other computer manufacturers to make use of “their” ingenious magnetic charging solution which they’ve included as “MagSafe” on MacBooks since 2008 — perhaps inevitably ruining the port and leaving me with only my iPhone and pens. I filled a few folded sheets of paper with my LAMY Safari (which is good, but overrated,) and felt quite ridiculous in the process. Thanks to my fiancé’s generosity, I type this bit now on her Panasonic R440 Electric Typewriter, which must still be considered a legitimate means of writing text in 2018 if only because of Instagram poetry. According to its rather dubious listing on Amazon, this model dates to September 4th, 1973, which is remarkable considering its spellcheck and auto-margin functions (neither of which I could actually figure out how to use.) If there is anywhere to be caught clacking away on a typewriter out of preference (I’d hesitate to call even my own situation one of necessity,) in 2018, it would undoubtedly be Portland, yet I am still extremely embarrassed to be the source of all this racket and would immediately perish if any of my neighbors bothered to track it down.

Even this very sophisticated example of the typewriting species is limited by one’s supply of both ink and erasing ribbon, though either can still be found for sale, remarkably. I am even less able to easily correct mistakes than those I wrote by hand because I feel a significant pang of pain via my mechanical empathy every time I use (or accidentally misuse) the function which whites out text with a sickening clunk. There’s something about this process which makes it feel more taxing, costly, and timeconsuming than any other, but perhaps with time and extended use, my embarrassment, empathy, and hesitance would fade and I’d become a cruel, loaded God of shitty prose, but I have no intention of finding out. I’ll willingly concede that restored or refurbished typewriters can be absolutely gorgeous, and there’s probably some validity in the “distraction-free writing environment,” but I’d suggest that anyone who’s pounded out any significant chunk of copy knows that one must find a groove of absolute focus within a word processor in order to complete work with any efficiency or cohesion, anyway. I’m as connected as any of you, yet these days, I always end up hyperfocused on Word, Dropbox Paper, and/or research in my browser to the exclusion of anything else on the machine, whether or not I intend to do so. I’m no authority, but I can’t see a functional place for a typewriter in 2018.

Portlanders, surely, are vain enough to avoid leaving such disastrous drafts laying about, though now’s a good time to note that one can now scan their typewritten document into a word processor using native software on their smartphone, nowadays, if they’re so unreasonably inclined. Using iOS default Notes app, I could scan this physical draft into Portable Document Format with just a few steps, but doing so would contribute to the ridiculous perception that Adobe’s ancient, clunky standard is the ultimate end of the line for any and all digital publishing. Yes, it’s ridiculous to consider “25 years” of development led to PDF 2.0’s release just last year, to nobody’s glee outside The Fucking Adobe Blog (which I do believe is running on Medium, hilariously.) Yet throughout my existence, it’s been the go-to half-step between text’s digital and physical forms. The liason, if you will.

Perhaps one could argue that this role in our collective academic Western word processing lives is profound (though no mentally functional human being wants to meet them,) which would inevitably lead them to criticize Adobe’s longtime occupation of it, but to examine the next significant step in the development of word processing is (this moment, at least) extremely hellish and alarming. This “Virtual Reality prototype,” for instance, surpasses even The Soul Ledger as the most distressing online video of all time.

Just 32.3% of survey respondents claim they print “at least one draft and use a pen or pencil to make notes/mark corrections by hand,” not including the additional 6.5% who “print at least one draft but make all corrections digitally,” leaving 61.3% who presumably do not physically print at all throughout their writing process. Our survey is broad, rudimentary, and not entirely scientific, yes, but I would bet these numbers would contrast significantly with those from respondents exclusively in academia. For myself and my colleagues, there remains “something” that can only be attained by physically manifesting written work, perhaps in requirement of tangible manipulation in order to thoroughly comprehend large bodies of information. As I’ve passed 100,000 words within the rough draft of my novel project, no amount of skimming on any sized screen has enabled me to catch the typos and inconsistencies which become immediately obvious as soon as I have the most current printed manuscript in my hands. I doubt even total immersion into one’s work via some VR-capable word processor would do much to assuage this discrepancy — or much at all, for that matter, aside from casting writers into their own special hell. Surely, only the most self-loathing of them would voluntarily choose to be so dunked. (Read: drowned.)